Crafting Vulnerable and Emotional Writing

Lessons from Jesmyn Ward’s “On Witness and Respair”

Photo: Jesmyn Ward’s website. Painting On the Sea of Time by Calida Rawles via Vanity Fair

Vanity Fair put out a special issue last week, named “The Great Fire”. Edited by legendary writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, the magazine captures the experiences of Black Americans as the country struggles with racial justice. While the entire issue was packed with exceptional writing, one essay that attracted a lot of attention was Jesmyn Ward’s essay “On Witness and Respair”. The story follows the author’s journey as she grieves her husband’s death while living through the pandemic and watching the Black Lives Matter movement. Her essay is truly special, and it offers valuable lessons on how to write about personal experiences in a way that is powerful and engaging.

Ward’s essay is an amazing opportunity to learn about great personal writing. I want to point out a few of the features that makes her writing so captivating. While you don’t need to read her article before proceeding, I encourage you to do so.

Creating Intimacy

Personal writing needs to create an intimate relationship between the writer and the reader. Abstractly, there is no reason the reader should “care” about what is happening to someone else. Bad stuff happens — that’s life. The author must create a bond with the audience so that the story has emotional stakes.

One of the best tools to create a rapport with your reader is the use of detail and anecdotes. No matter what personal writing you are doing, details are an essential tool for the audience to see the world from your eyes. This doesn’t need to be done through long over-wrought descriptions of an event or setting; brief snapshots can be just as impactful. Take this line:

He traveled with me often on business trips, carried our children in the back of lecture halls, watchful and quietly proud as I spoke to audiences, as I met readers and shook hands and signed books.

This moment is so sweet. I immediately picture a hulking man at the back of a wood-paneled auditorium, silently bobbing up-and-down in the “carrying a baby” shuffle that dads do. Just a peak into the Ward family makes you fall in love, pulling you into the story.

Emotional writing is also very challenging when it comes to sentence-level writing mechanics. The author needs to find language that is evocative and engaging, but not melodramatic. On this count, Ward’s writing is simply amazing. The whole essay is loaded with what feels like one-sentence poems, each packing an emotional punch. Here is one of my favorites:

Without his hold to drape around my shoulders, to shore me up, I sank into hot, wordless grief.

Sentences like these ask a lot of an author’s writing abilities. If you concentrate on the use of commas, you will notice the sentence has an unusual construction. Ward chose a structure designed to end on “grief”. Grief is one of the themes of the essay, and this is the first use of the word, so it is impactful for it to appear as the last word of the first section of the article.

Word choice is also demanding. “Draped around” could be “cover”, “hot” could become “burning”, and “wordless” could be changed to “silent”. A quote attributed to Mark Twain reads “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is… the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.” I don’t quite buy into the idea of a “right” word, but Ward had to make a lot of choices when composing this line. Sentences like this require additional attention to make sure it has the right impact. It is sometimes useful to rewrite sentences like this multiple times to find the best fit. Not every sentence requires this level of effort, but this line was clearly meant to be pivotal, so the author probably put extra thought into getting it right.

Thesis-Free Writing

Ward’s article did not have an argument, or even a specific “moral of the story”. This may seem obvious, but many authors have been conditioned to write in a thesis-centric mindset. Almost every article I read is constructed to share information or presenting an argument. Even personal essays are typically built around a particular life lesson. “On Witness and Respair” does not follow this formulation, and lets us sit with the author as she processes her experiences over the past year.

This isn’t to say this article didn’t have meaning. In my reading, this essay is a profound reflection on grief, and the particular legacy of grief that has followed Black people for hundreds of years. It is also about solidarity and hope. Ward offers a deep exploration of these subjects without “making an argument”.

Emotional and vulnerable writing doesn’t need to be thesis-free. There are plenty of great argumentative pieces that use personal and emotional moments as part of the writing. This is simply a reminder that a thesis-centric structure can create a barrier to exploring certain topics.

Using Form As A Tool

Ward’s use of form and style in this article is stunning. She uses dramatically different structure and rhythm to convey different emotions. Take this paragraph:

During the pandemic, I couldn’t bring myself to leave the house, terrified I would find myself standing in the doorway of an ICU room, watching the doctors press their whole weight on the chest of my mother, my sisters, my children, terrified of the lurch of their feet, the lurch that accompanies each press that restarts the heart, the jerk of their pale, tender soles, terrified of the frantic prayer without intention that keens through the mind, the prayer for life that one says in the doorway, the prayer I never want to say again, the prayer that dissolves midair when the hush-click-hush-click of the ventilator drowns it, terrified of the terrible commitment at the heart of me that reasons that if the person I love has to endure this, then the least I can do is stand there, the least I can do is witness, the least I can do is tell them over and over again, aloud, I love you. We love you. We ain’t going nowhere.

One sentence. This frenetic line captures the anxiety of living through COVID, where one terrified thought tumbles out on top of the next. The rhythm is breathless and unsettling.

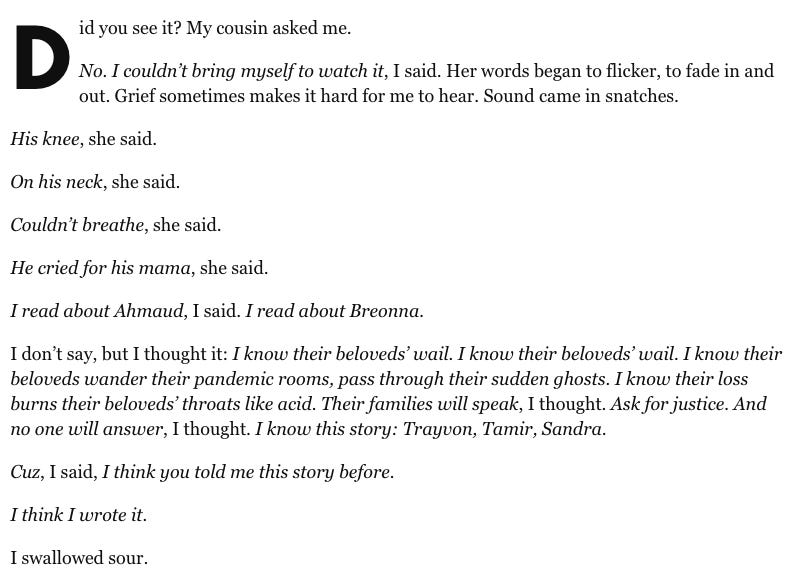

Now read this section (I have embedded a picture to preserve the formatting):

Source: Vanity Fair.

This reads like a stand-alone poem. Here, Ward is using a powerful beat to create a feeling of purpose and weight. She leaves most of “this story” off the page, allowing us to fill in the blanks. The implied message: we all know this story already, and we’ve known it for years.

In both cases, Ward manages to convey so much more than what is literally on the page. It would have been possible to rewrite these sections in a more “conventional” way, but it would lose so much depth. While this variation in style might not be suitable for every piece, it is worth considering how you can leverage stylistic shifts to enhance the emotional impact of your writing.

Ward’s essay is brilliant. I feel strange commenting on an article this personal, but there is just so much to learn from her writing. As someone who struggles to execute on an emotional tone, reading this article taught me a tremendous amount. Honestly, I feel I have barely scratched the surface of what made this story so good. I look forward to read more of her work in the future.

Contact/about the author: email, Twitter, medium profile, website.